Reducing loss of muscle and strength

There has been enormous progress in bringing down the death rates for older people over the last 50 years. We are now facing an increasing size in our elderly population and leading thinkers are questioning whether the focus of medicine should move away from mortality to improving function. In other words, maintaining the ability to live independently (health span) may be more important than prolonging life (lifespan) in the very elderly. One of the critical determinants of health span is loss of muscle mass and strength which has been termed sarcopenia. Sarcopenia can prevent someone getting out of a chair, climbing the stairs or leaving the house.

Previously, sarcopenia had been thought to be just a natural part of the ageing process. It is well known that a person’s grip strength gradually declines from the age of 30 with acceleration in decline after the age of 60. There is a threshold at which the natural decline impacts on function and can be termed pathological. This is similar to dementia, where the natural loss of brain neurons is sufficient to cause functional memory problems, or to osteoporosis where the natural loss of bone density is sufficient to make the fracture risk unacceptably high. Research into sarcopenia is very much in its infancy. There has yet to be agreed an international definition or threshold set. This is because previously people had not lived long enough for the effect of reduced muscle mass and function to be a significant problem. There is increasing evidence that as muscle deteriorates, chemicals called myokines are released into the bloodstream. These are found to affect many other organ systems. It may be that the aging of the muscle sets the pace for the aging of other tissues and potentially the whole body.

There does not appear to be just one process responsible for sarcopenia and there are a number of promising drugs, which hope to slow down the process, undergoing clinical trials. Researchers have identified a number of lifestyle changes we could all try to adopt to reduce sarcopenia:

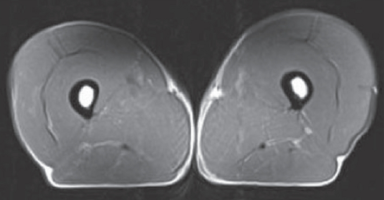

1. Increase weight or resistance training (aerobic exercise on its own has little impact on reducing sarcopenia). Compare and contrast the two MRI scans below looking at a cross section of the thigh. The top scan is from an inactive 74 year old man showing wasting of the muscles and increased fatty adipose tissue. The middle scan is from a 70 year old triathlete which shows preserved thigh muscle not too dissimilar to the bottom scan from a 40 year old triathlete.

Images from Wroblewski, A et al (https://www.slideshare.net/mayayo/chronic-exercise-prevents-aging-wroblewski-amati-sep2011?mc_cid=e741e84686&mc_eid=dfc91c7071)

74 year old sedentary man

70 year old triathlete

40 year old triathlete

2. Increasing the amount of protein consumed by over 65s (The European Geriatric Medicine Society recommends 1.0-1.2mg of protein per kilogram bodyweight per day)

3. Reducing vitamin D deficiency (current government recommendations are for 10mcg (400 IU) vitamin D a day for over 65s)